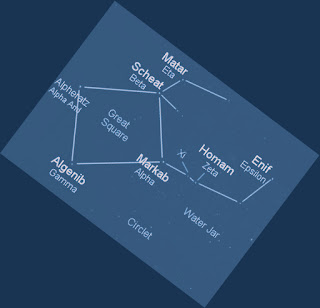

Pegasus star map by James B. Kaler

Pegasus star map by James B. KalerOne of the ways astronomers gauge sky quality and extent of light pollution at a given location is by counting how many naked-eye stars they can see inside the Great Square, the area bounded by the stars Alpheratz, Algenib, Markab, and Scheat.

Let’s try it. With a group of people, it can be fun to compare all the different star counts. Even at the same location, naked-eye counts may vary a bit due to each individual’s visual acuity, age, fatigue level, and observing experience. Not to mention vivid imagination and propensity for cheating.

1) To see the maximum number of stars you can, you should dark adapt before beginning your count. Dark adapting involves avoiding exposure to all white light for a minimum of 20 minutes before an observing session. No lamps, no TV, no house lights, no headlights, no street lights. You may have to live with some diffuse white light in the general vicinity (hard to avoid it in most neighborhoods), but do not look directly at unshielded bulbs. Use a red light flashlight if you need light to safely walk around.

The reason for this strange preparatory ritual is that your night vision is greatly enhanced by the restoration of chemicals in your eyes that were ‘bleached’ by light. This restoration occurs in the dark, and the longer you linger in the dark, the easier it will be to see faint stars. Trust me, dark adapting does make a difference.

Example of red light flashlight from www.celestron.com

Example of red light flashlight from www.celestron.com2) Start your observing at least one hour after sunset. It will be dark by then, and winged Pegasus will be well positioned, flying high in the sky. Generally speaking, the transparency of the night sky is better up near the zenith than down near the horizon because near the zenith we are looking through less atmosphere, aka “gunk.” Transparency means atmospheric clarity, and good transparency can mean the difference between seeing objects clearly and not seeing them at all. Be aware that transparency can be negatively impacted by clouds, haze, dust, or humidity.

3) At first glance, the Great Square is a blank slate. In fact, in the city or other light-polluted environment, you may not be able to see any stars inside the Square. Observing from a darker location is best. From my semi-rural backyard, I can see five stars inside the Square. From a rural location, it is possible for a person with good eyesight to see 12 or more stars. From an isolated location where the sky appears carpeted with stars, a person with keen eyesight may see 20 or more stars.

How many can you see? (Note: don’t count the four corner stars in your total.) Please share your count in the Comments section below, and be sure to tell us your location (city/state/province/country).

Johann Schmidt, Director of the Athens Observatory during the late 1800s, is reported to have counted 102 naked-eye stars inside the Great Square. Can you imagine?! This was before the proliferation of electric streetlights, so the nighttime environment world-wide must have been magnificently black-cat-in-a-coalbin dark.

4) If you have binoculars, train them on the Square’s interior after you’ve finished your naked-eye count. Now you can see that it’s packed full of stars--dozens and dozens of twinkle lights of the Milky Way galaxy. Some are nearer to Earth than the corner stars of the Square and others sparkle hundreds of light years beyond them. We may not see the three-dimensionality of the night sky, but we can certainly imagine it. Sweep your binoculars around in there, and savor the moment.

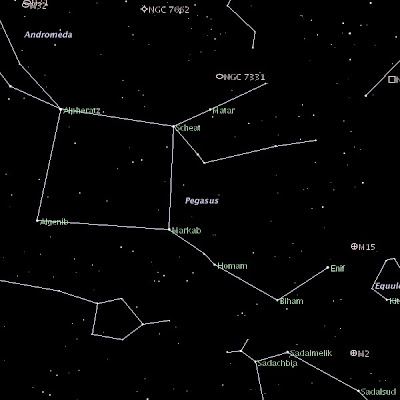

5) To continue our bino-viewing, let’s goggle at one of the showpiece globular clusters of the Milky Way, which resides just off the horse’s nose. M15--short for Messier 15--is a dense ball of gravitationally bound stars.

There are 150 known globular clusters in our Milky Way galaxy. Globulars contain thousands to perhaps millions of stars and are among the oldest objects in the universe. Locate M15 by extending the imaginary line between Biham (pronounced bih HAHM) and Enif, half again as long past Enif. Then train your binoculars on that spot. If you spy a round, fuzzy object, you’ve found M15. Feel free to let loose with a celebratory whinny! In a six-inch or larger reflector telescope, you should begin to resolve the stars in the cluster, that is, they should begin to separate into distinct points of light.

6) The Great Square is a window not only on the Milky Way, but also on the universe beyond. Skilled amateurs with large telescopes are able to view over 100 distant galaxies through the giant, floating window frame of the Square. But the brightest galaxy in Pegasus, the unromantically-named NGC 7331, lies outside the Square. You’ll need at least a six-inch reflector telescope to see it. Look northwest of the star Matar (pronounced MAH tahr) to find this spiral galaxy, sometimes referred to as the ‘twin’ of our galaxy, also a spiral.

Although NGC 7331 is the centerpiece of a noted galaxy group called the “Deer Lick Group,” you won’t see the other four faint galaxies without a large telescope. They are far more distant than the whorled beauty NGC 7331, itself an incomprehensible 49 million light years from Earth.

6) The Great Square is a window not only on the Milky Way, but also on the universe beyond. Skilled amateurs with large telescopes are able to view over 100 distant galaxies through the giant, floating window frame of the Square. But the brightest galaxy in Pegasus, the unromantically-named NGC 7331, lies outside the Square. You’ll need at least a six-inch reflector telescope to see it. Look northwest of the star Matar (pronounced MAH tahr) to find this spiral galaxy, sometimes referred to as the ‘twin’ of our galaxy, also a spiral.

Although NGC 7331 is the centerpiece of a noted galaxy group called the “Deer Lick Group,” you won’t see the other four faint galaxies without a large telescope. They are far more distant than the whorled beauty NGC 7331, itself an incomprehensible 49 million light years from Earth.